The heartwarming story of a young man and his 30-page paper.

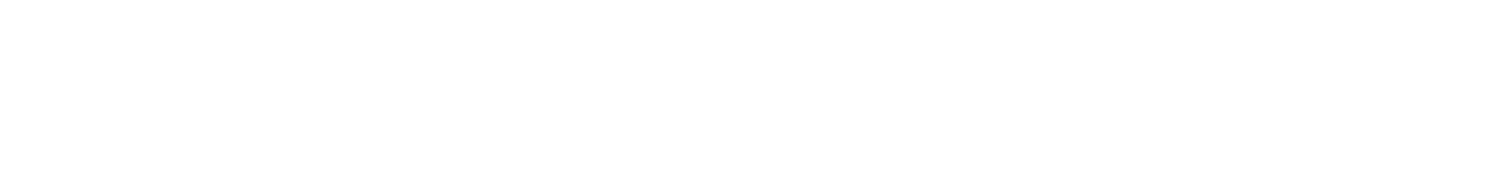

Optimus Primer is a software tool for working on literacy primers for low-density languages.

Megan's training equips her to transition from teach missionary kids to developing literacy programs that start kids off learning in the language of their hearts. Read more to see why this matters.

Megan taught maths, English and Spanish at Rain Forest International School in Yaoundé, Cameroon in 2010–2012.

Alex was a network system administrator in Cameroon.

Natural language generation tech may help get scripture into the hands of nondominant language communities faster.

I plan to conduct research and empower Cameroonian educators so that the children they teach can enjoy the economic, social, and spiritual benefits of literacy.

There was just one stop between us and Disney World: a museum tour. The guide had us read identical passages from the same book in two languages: Denya and Hawaiian Pidgin. The first reader’s eyes grew wide at the sight of her incomprehensible script.

Genó ɛyigé na gekoge, nke mpɛle, ngɛ njuné bɔɔ́ abi yɛ́ muú álá ákágé pa fɔ́….

She gave up. The Hawaiian Pidgin was easier.

Afta dat, jalike one dream, I wen look, an dea in front me had uku plenny peopo! Dey so plenny dat no can count um. Dey come from all da countries, all da ohanas, all da diffren peopos, an all da language all ova da world. Dey stay standing in front Godʼs throne, an in front da Baby Sheep Guy.

The idea that Hawaiian Pidgin could be written was completely foreign to me; people don’t write Hawaiian; they just speak it. But here it was in Wat Jesus Show John 7:9 of Da Jesus Book (Revelation 7:9 in the Bible). The guide explained the meaning of the activity to us: just like he expected us to read the Bible in Hawaiian and Denya, which we don’t understand, we expect people all over the world to read in English, which they don’t understand.

Moreover, the Bible has had more influence on my life than any other book. I grew up reading it in an arcane dialect and caring little about it, but my life changed when I read a translation that sounded like I talked—with no thees or thys. I could partly pick apart the Hawaiian translation with great effort, but it had no chance of meaning to me all that the English does. My experience is captured by the words of Nelson Mandela, "If you talk to a man in a language he understands, that goes to his head. If you talk to him in his own language, that goes to his heart."

That is the day I was first moved to play my part in language development to right this unjust double standard. As a computer scientist, I’d never expected to be in language development, but having seen the power of language, I quickly came to see similar gaps in technological literacy and opportunities to support language development with technology.

The world is limited in its understanding and ability to address global issues because the interfaces we use to collaborate are limited to a few powerful languages and people groups. I am pursuing a Master of Science in Human-Computer Interaction at University of Maryland so that I can bring useful computer interfaces to field linguistics and literacy to empower marginalized people groups.

Language Gap

There are about 7000 languages, few of which have a preferred status like English, French, Spanish or Mandarin, nor access to good teachers and resources to learn them. This is about more than language preservation and diversity. Speakers of these languages are cut off from civic influence, economic opportunities and education. For example, children who speak minority languages at home and in their village go to school for the first time and are expected to learn in a language they don’t know. Sadly, School Effectiveness for Language Minority Students’ by Thomas and Collier shows that the only way for children who speak a minority language to achieve educational parity with their majority language peers is to be taught for at least six years in their own language.

Language Development

Organizations like SIL International address the language gap by mobilizing communities to develop resources and competencies for their languages. SIL employs the greatest number of field linguists in the world to document and develop minority languages, creating dictionaries, grammars and even writing systems. Publishing new and translated books like literacy primers, textbooks, story books and Bibles gives languages a body of valuable literature that motivates literacy. The multilingual education movement, in which students begin school in their own language and gradually transition to a majority language, has markedly improved schools in all metrics of success.

In The Power of the Local, SIL Senior Education and Literacy Consultant Barbara Trudell illustrates the difference that mother tongue education can make,

This morning, a teacher in a remote Kom village picks up his lesson plans for the day and turns to his class of 55 bright eyed and energetic grade one pupils. Holding up a drawing of a chicken, he speaks in Kom language: “What is this?” A dozen voices answer, volunteering that this chicken is in fact a speckled hen and that their mother or neighbour has one just like it. The lively discussion that ensues includes writing the Kom word for ‘chicken’ on the blackboard and talking about the uses and care of fowl.

A few miles away, another teacher in a similarly remote Kom village turns to his similarly bright eyed, if bemused, grade one pupils. “Class, stand up!” he says in English, and the class straggles to their feet. “Sit down!” he then orders…. He draws a picture of a chicken on the blackboard, and says to the children in English, “This is a fowl. Repeat with me. This - is - a - fowl.” The children obediently respond to his gestures: “This - is - a - fowl,” they all intone.

Politically, countries like Uganda (41 languages) and Cameroon (280), are supporting multilingual education with legislation, but there is a great deal of work to be done before it can be a reality that changes lives. It will require great effort and the dedication and teamwork of communities to accomplish. In SIL’s early days of language development, a small team of expatriates made all the meaningful materials. Through research and humbling experiences, SIL found its first methods unsustainable and unempowering, transitioning to building up local colleagues. Now, translation teams and committees consist often entirely of native speakers.

The Interface Gap

With so many new laborers for language development, many who are computer illiterate are being asked to use computer programs to document, analyze, document and publish. This has resulted in a great workforce being mobilized to teach technological neophytes which buttons to press, but there should be more work flexing interfaces to their needs or teaching concepts of computer literacy. In this context, I realized how forcing nationals to use foreign interfaces paralleled the Kom teacher drilling his students in a colonial language.

In the same way that a language gap keeps the marginalized from participating with their more powerful neighbors, so too an interface gap keeps out the technologically and literally illiterate. The ICT4D 2.0 Manifesto (Heeks 2009) names two priorities for interface innovation

- interfaces for the illiterate (audio-visual interfaces) and

- interfaces for all local languages.

To address this need, I hope to use my HCIM to directly support language development with technology that meets needs and increase technology literacy alongside those improving mother tongue literacy. Currently, locals serve as system administrators and computer help desk workers, but there are few people in minority people groups and language development with suitable interfaces or the power to make them. By teaching locals more advanced technology like programming and application development, I can multiply their power and equip them to create more contextualized technology than what expatriates can provide.

One of the biggest obstacles to literacy in minority languages is a dearth of teaching materials and written content in local languages which are desirable enough to excite students to read. I can contribute by helping minority language communities get their language materials on the internet, building platforms for local and digital publishing, and researching techniques for distributing educational materials. Lastly, developing language data management policies and technologies will remove obstacles for sharing, collaborating, and distributing language materials.

Conclusion

By the end of that tour, I’d stopped thinking about Disney World; I had bigger things on my mind. I took a year off from school to teach language abroad and serve SIL in Cameroon. As a professional, I’ve worked alongside language analysts, made interfaces for them, and learned computational linguistics from scientists at CASL, but I want more training before I return to SIL. I'm growing in my skills in a professional setting as a researcher, and I'm pursuing a Master of Human-Computer Interaction degree. This will prepare me to make a positive impact on the language development community and thousands of minority language groups.

Alex has been involved with The Wheelock Conference at Dartmouth since it's beginnings in 2010.